BY SAM DESTEFANO

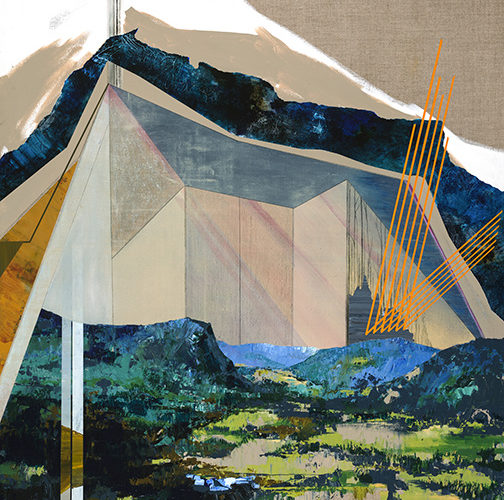

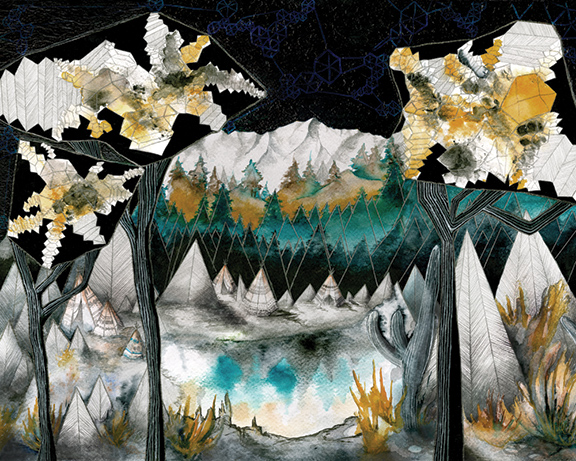

The art of Noelle Phares is nothing short of mesmerizing. You can get lost in her pieces, the depth of the colors combined with geometric shapes gives you a sense that she has a story to tell.

At what point did your work as an environmental scientist cross paths with your art? Is this a symbiotic relationship, each deepening your vision of the other? In other words, does your art help you to think about the environment and does your environmental science background inform your art?

At what point did your work as an environmental scientist cross paths with your art? Is this a symbiotic relationship, each deepening your vision of the other? In other words, does your art help you to think about the environment and does your environmental science background inform your art?

I’ve always been a creative. Although it wasn’t until about 2 years ago that I made the decision to embrace a new identity as a true artist, not just a creative. It seems like most jobs these days allow for the cultivation of many different roles and skillsets under a single job title umbrella, as was my experience. So as I worked through my early careers as a biochemist and later as an environmental scientist leading a product team for a technology company after graduate school, I sought out avenues for visual creativity. In the latter role, which was my last before making the transition to fine art, this meant taking the reins on a lot of graphic design for product marketing, educational informatics, and pitch decks for the agricultural data products my team built. I just gravitated to it.

But a career as a painter had always been a pipe dream for me. I’ve had this whimsical vision in my mind for as long as I can remember: myself in overalls covered in paint, spending my mornings in a second-story, brightly lit and plant-laden art studio on the second story of a house overlooking the Pacific Ocean, painting the landscapes that swirl around in my mind. Idyllic, right? My twin sister can attest that I’ve daydreamed of this for a long time. The prospect of putting all of my energy into bringing the images I find most fascinating to life in a physical manifestation, and figuring out how to share those widely so as to change others’ perspectives on landscape + society, checked so many boxes for me but seemed entirely impractical. I didn’t have any models for what a career in the arts looked like. I’d grown up with parents in medicine, and had always been drawn to the hard sciences despite my subterranean desire to scrap that world for something looser, something more colorful.

Four years ago I met my now fiancé. His mother, Amy Metier, is a prominent professional artist in Colorado. Both acquiring a new artist role model and a partner sincerely empathetic and respectful of career artists, spurred me to reconsider my naiveté with regard to how honorable and fiscally feasible a life in the arts could be. And so began my departure from the hard sciences, and the beginning of a new chapter for me wherein I aim to contribute to the environmental movement from an entirely different angle.

We love the marriage of the geometric shapes and lines in your work. Do you feel that the abstraction of nature in your art conveys a positive or negative depiction of our environment’s current condition? Does the abstraction relate to this idea in any way?

We love the marriage of the geometric shapes and lines in your work. Do you feel that the abstraction of nature in your art conveys a positive or negative depiction of our environment’s current condition? Does the abstraction relate to this idea in any way?

As a scientist, my work centered around using big, geospatial datasets to better understand how growing systems (aka agriculture) use resources, and employ those understandings to build models that enabled growers (aka farmers) to waste less water, chemical, labor, etc. This required thoughtful interrogation into how humans alter their landscapes, how these alterations impact other ecosystems and populations, and just how many components must be considered to characterize a landscape and understand how it will change over time. Breaking lands into data layers spawned in me a new way of thinking about terrain, as I began to see areas of land as the compilation of numerous distinct, yet highly relational layers of information stacked on top of each other. I realized from an analytical perspective that landscape is not simply what is visible by the naked eye. There are boundless unseen forces that act upon any given space over time, and will continue to do so to shape how it physically presents itself, both functionally and aesthetically. When I paint now, I harken back to those learnings to reimagine the presentation of an environment. To evoke the unseen. I think these two worlds of mine will always feed each other.

You’re correct in your assertion that the marriage of geometric, architectural shapes with organic landscape forms in my work is symbolic of the current condition of the environment. To explore this more, I’ll harken back to an essay I composed for Range Magazine last year entitled “Frontiers of the Anthropocene.” This title really embodied the subject of my growing body of work. To me, the proof that we are indeed living in the “Anthropocene” – a term which denotes the current geological age during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment – is precisely evident in the degree to which you see both of these seemingly contradictory worlds collide. Against the backdrop of almost every wild landscape sits the evidence of man, visible in the starkly geometric presentation of our buildings, our roads, our power lines, our grids. While I often hear people remark over how unique the confluence of both landscape and geometry are in my work, I ask them to realize that this is not really unique at all. This is what the world looks like, increasingly so as our urban boundaries push outwards. However, instead of condemning this truth, I challenge us to reconsider the frontier notion that urbanity and nature are diametrically opposed. A world in which these two sit hand-in-hand, feeding each other and respecting each other, is so much more hopeful. In fact, that is how the rest of nature functions, is it not? In symbiosis instead of in opposition to the rest of life forms on Earth? Normalizing the notion that development can be complementary to nature is my way of encouraging the designers of the world to more carefully consider the impact of their designs.

Tell us about your creative process. Is there music playing? Are you in the studio? Where does most of your work take place?

Tell us about your creative process. Is there music playing? Are you in the studio? Where does most of your work take place?

All of my work references landscapes I’ve either been to or would like to visit someday, but most of the actual painting takes place in my studio. As I work larger and larger, it has become difficult to do much plein air work because I need big canvases, or paper that is too large to carefully preserve outside of the studio. In addition, the mixed-media nature of my painting requires me to have a lot of different paint mediums on hand. I find that the best way to produce efficiently and effectively is to avoid wasting time moving it all around often.

The business components of my practice have become a full time job these days, before the painting itself even comes into play. This includes marketing, sales, web, customer service, retail/wholesale relationships, framing, order fulfillment, new product design… the list goes on. I now have a number of people who help me with these other elements, including an assistant who now does most of my framing and order fulfillment. But I’ve had to get better at maintaining a schedule that still allows for the actual painting work to happen. I’m a night owl by nature, which serves me well as I’m able to spend days solving business problems and evenings painting. When my fiancé goes to bed, I slap the headphones on and get to work. When I’m excited about a piece, or up against a hard deadline, it’s not uncommon for me to be painting until 3am. Although it’s usually when I’m up that late that I’m enjoying it the most.

Do you see your work as evolving? How would you describe its beginning in relation to where you are now? Also, do you have a vision for where you’re heading in the future?

Do you see your work as evolving? How would you describe its beginning in relation to where you are now? Also, do you have a vision for where you’re heading in the future?

One of the key places that I’ve seen my practice evolve is in the evolution of my creative process. As I move towards showing more in galleries, the need to produce larger paintings has risen. Where I used to employ high levels of detail in every inch of every piece, I have been working to change that to enable producing larger works without a proportional increase in the time needed to complete them. I am getting better at designing compositions that require fine detail only in the portions that are designed to draw the eye, and allowing myself to use broader strokes and negative space in the remainder of the piece.

I’ve also been deliberately improving the efficiency of my design phases. By the time I put paint on canvas or paper, a significant amount of time has already been spent calculating palette, subject and composition. In the past I did this all on sketch paper and in my mind, but as I increasingly employ digital tools to perform this experimentation, my paintings are becoming more interesting and the design iterations are getting quicker.

I’d like to keep building out my body of work that explore the vulnerability of certain landscapes to human development. A goal of mine would be to work towards more powerfully combining my hard science background with my fine art practice, perhaps by partnering with working natural scientists to put on shows that combine the presentation of my landscape art with the presentation of more technical talks about those landscapes and what imperils them. I would love to publish an art book along these lines in the not-too-distant future.

Where can we see your work?

My newest body of original work is on exhibition at Space Gallery in Denver’s Santa Fe Arts District until July 17. Beyond that, I will be showing locally at the Pearl Street Arts Festival at the end of July, and the Jackson Hole Art Festival in August. I always sell prints through my website and through a number of retail shops, both locally and elsewhere. I’ve been working with a prominent international outdoor company to release an apparel line featuring my artwork for Spring 2020, and I’m at the early stages of planning for a solo exhibition in 2020, details for both forthcoming.

We urge you to get to know the lovely Noelle on a deeper level. Visit her at www.noellephares.com AND Instagram @noellephares.